Recent economic indicators point to the weakening vitality of the Korean economy shored up largely by an increase in exports.

Business sentiments remain pessimistic as manufacturing and construction sectors are suffering setbacks. Core inflation, which excludes volatile oil and food prices, has dropped to an 18-year low, reflecting sluggish domestic demand.

Manufacturing output shrank 6.6 percent from a year earlier in December, following a 1.7 percent on-year decline in the previous month, according to data released by Statistics Korea last week.

Construction orders decreased 17 percent in the fourth quarter of last year from the same period of 2016 after recording a 10.9 percent fall in the preceding quarter.

The average factory operation rate remained at 70.4 percent in December, the lowest since August 2016, when the figure was at the same level.

For all of 2017, the rate stood at 71.9 percent, the lowest since 1998 in the aftermath of a devastating foreign exchange crisis, when factories ran 67.6 percent on average of full capacity.

Industrial production as a whole rose 0.2 percent in December from a month earlier, decelerating from a 1.3 percent gain in November.

The output increase was attributed mainly to a rise in the service sector production, which came despite a slump in retail sales.

Production in the service sector increased 0.2 percent on-month in December, with retail sales sinking 4 percent, compared to a 5.7 percent gain in the previous month.

Releasing the latest industrial data, an official at the state statistics office said the overall economic recovery “is still being maintained.”

But the view does not seem to be shared by most economists, who express worries about increasing signals that the Korean economy is losing, not gaining, traction, partly held back by antibusiness policies pursued by President Moon Jae-in’s administration.

Policymakers hope Asia’s fourth-largest economy will continue to grow over 3 percent this year following a 3.1 percent expansion last year.

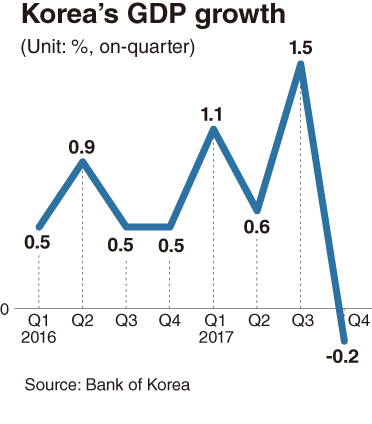

But an unexpected negative growth in the fourth quarter of 2017 is casting a shadow on the possibility such a forecast will be realized.

Data published by the Bank of Korea last month showed the country’s gross domestic product decreased 0.2 percent from a year earlier in the final three months of last year.

It marked the first negative quarterly growth since the fourth quarter of 2008, when the economy contracted 3.3 percent, hit by a global financial crisis.

BOK officials said the economy has kept robust growth trend, cautioning against exaggerating the implications of the latest quarter’s negative record, which they attributed partly to a high base effect from a 1.5 percent expansion in the preceding three-month period.

But many economists note the negative quarterly growth should still be seen as signaling economic vitality is weakening amid a downturn in manufacturing output, facility investment, construction orders and domestic spending.

Korea saw exports, which have shored up its economic growth, soar 22.2 percent from a year earlier to more than $49.2 billion in January on brisk shipments of memory chips and petrochemical products, according to recent government data.

The prospect for a continuous increase in exports, however, is being overshadowed by the strengthening of the won against the US dollar, rising prices of oil and other commodities and mounting protectionism in the US and other major economies.

The grim mood spreading through corporate circles was reflected in the business survey index compiled by the central bank.

The index, based on a survey of 3,313 local firms, stood at 78 in January, turning downward in three months. The figure came in further down at 63 for small and medium-sized enterprises and 71 for companies reliant on domestic sales.

A reading below 100 means the number of companies forecasting their businesses will deteriorate in the coming month was larger than that of firms expecting improvement.

Experts express concerns that the business sentiment index and other economic indicators will continue to worsen as the impacts of the Moon administration’s policies set to increase corporate costs will be felt more acutely down the road.

The administration has pushed to increase the minimum wage, shorten work hours and turn temporary jobs into permanent ones as part of its income-led growth strategy.

In the BOK survey of local companies, published last month, 9.1 percent of manufacturing firms said they were having difficulties coping with rising labor costs and manpower shortages, compared to 4.7 percent in May last year, when Moon took office.

“It is not easy to overcome negative factors (faced by the Korean economy) this year only through income-led growth initiatives,” said Ju Won, a researcher at the Hyundai Research Institute, a private think tank.

He noted deregulation and other policy efforts need to be stepped up to enhance the business environment and boost corporate investment.

An annual symposium attended by local economists, held in a provincial city last week, turned into a stage for criticizing the Moon government’s economic policies.

Cho Jang-ok, a professor at Sogang University, warned that pushing for pro-labor policies recklessly without considering labor productivity would cause Korea to undergo “Japan’s lost two decades” of economic recession in the 1990s and 2000s.

By Kim Kyung-ho

([email protected])