Impressive trade figures logged by Korea this year have veiled the weakening competitiveness of its major manufacturing industries, analysts here say.

The country’s outbound shipments in the first 11 months of the year reached a record-high $524.8 billion, up 16.5 percent from a year earlier, according to data from the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy.

Riding on the surge in exports, Asia’s fourth-largest economy saw its annual trade volume exceed $1 trillion last week. Korea’s trade volume surpassed the landmark figure for four consecutive years from 2011 before missing that mark in the following two years amid the global economic slowdown.

What is worrying is that many of the country’s key manufacturing industries have been losing competitiveness in global markets.

In November, Korea’s overall exports rose 9.6 percent on-year, but the outbound shipments of its 13 major export items increased at a slower pace of 7.8 percent, according to figures from the Korea International Trade Association.

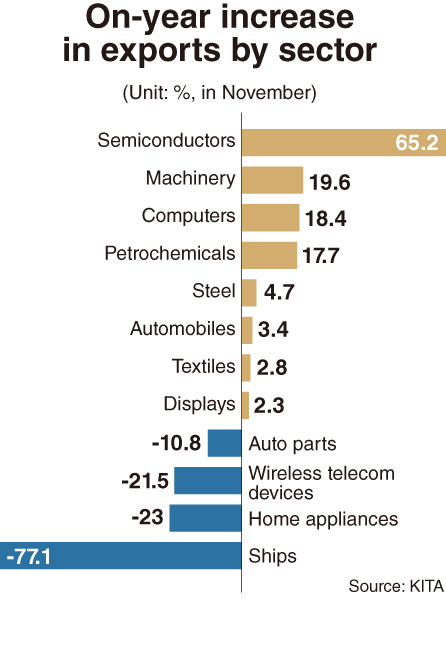

Exports of ships, home appliances, wireless telecom devices and auto parts declined 77.1 percent, 23 percent, 21.5 percent and 10.8 percent, respectively.

Overseas shipments of steel, cars, textiles and displays recorded modest increase rates each at 4.7 percent, 3.4 percent, 2.8 percent and 2.3 percent.

Only five goods — semiconductors, petroleum products, machinery, computers and petrochemicals — exceeded the average growth rate of the country’s exports last month.

Such major items’ proportion of Korea’s exports was down from 80.6 percent in 2014 to 78.3 percent this year.

A recent report from the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics and Trade, a state-run think tank, said the increase in the country’s exports is projected to decelerate to a single digit next year partly due to the base effect.

It forecast outbound shipments of major export items will grow 4 percent in 2018, slower than the overall export growth rate estimated to reach 5.3 percent.

The biggest challenges for Korea’s manufacturing exporters are posed mainly by Chinese rivals increasing capacities and enhancing technologies at an alarming pace.

China has caught up with Korea in traditional manufacturing industries such as steelmaking and shipbuilding.

A recent study by the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology showed the technology gap between Korean and Chinese companies in semiconductors and displays has narrowed to a couple of years.

China has raised more than $100 billion in funds to nurture the semiconductor industry. It is pushing for the construction of 15 semiconductor factories over the years through 2019, compared to three in Korea, four in Japan and seven in Taiwan.

Chinese companies also plan to build seven more plants to produce liquid crystal display panels from 2018 to 2020, exacerbating a glut in the market.

What particularly worries analysts here is the Korean economy’s overreliance on semiconductors that have propelled the country’s exports in recent years. In the first 11 months of the year, semiconductor exports soared 65.2 percent on-year.

A slump in the semiconductor industry could blow a severe blow to the economy, reducing exports and facilities investment, they say.

The KIET report forecast semiconductor exports will increase 22.9 percent in 2018 from a year earlier, with its proportion of the country’s total exports rising from 17 percent to 19.9 percent.

The Institute for International Trade, a research arm affiliated with the KITA, predicted semiconductor exports will rise 8.8 percent on-year in 2018.

But a recent report from the Korea Development Institute, a state-run think tank, cautioned against the rosy prospect for semiconductors. It noted increased production capacities of Chinese chipmakers would start to counterbalance a rise in demand on the back of a widening range of products equipped with artificial intelligence and Internet of Things technologies.

“It is hard to expect semiconductors to make as much contribution to exports as this year down the road,” said Jeong Dae-hee, a KDI researcher.

He said the problem with the Korean economy is it has no other sector to effectively offset a possible slowdown in the semiconductors industry.

Kim Chang-kyung, a professor of science and technology policy at Hanyang University, said it is only a matter of time for Chinese chipmakers to take up most of the vast local market, noting Korea should have a sense of crisis it will hand over the lead in high-tech sectors to China.

Critics say President Moon Jae-in’s administration has paid little heed to bolstering the country’s industrial competitiveness, while pushing for income-led growth by creating more jobs mainly in the public sector and expanding welfare programs.

Since it was launched in May, economy-related ministers and presidential aides have held no meeting to discuss ways to boost industrial and corporate competitiveness.

In a report on industrial policy direction, submitted to the National Assembly on Monday, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy said it will focus on advancing five innovative sectors, in which it aims to create over 300,000 jobs by 2022.

The five prioritized areas are self-driving cars, renewable energy resources, bio-health, the Internet of Things and semiconductors and displays. The ministry plans to come up with detailed implementation plans for each sector by the first quarter of 2018.

Economists say the Moon administration should carry out regulatory and labor reforms to forge business conditions fit for the era of the “fourth industrial revolution.”

Corporate circles are frustrated with its passiveness toward reform tasks, as shown in its refusal to push through the enactment of a bill introduced by the previous administration to set up regulation-free zones aimed at nurturing new industries.