SEJONG — The manufacturing industry has come to a standstill in output and productivity that could further weaken the nation’s already lackluster economic growth, which has suffered as a result of sagging exports and weak private consumption.

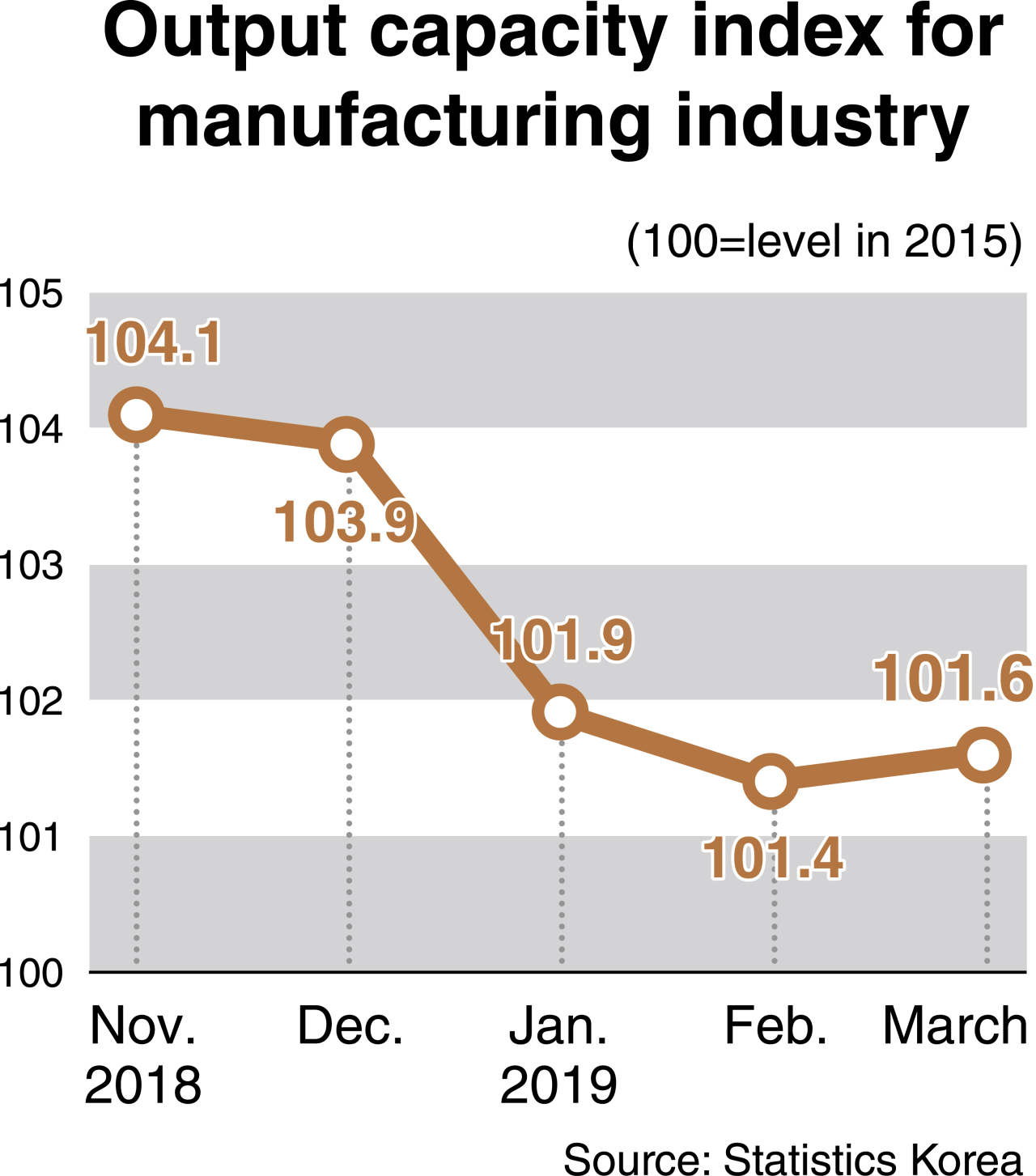

According to Statistics Korea, the manufacturing production capacity index stood at 101.4 in February 2019 — the lowest level in 33 months, since May 2016, when it posted the same figure.

Though the index inched up to 101.6 in March 2019 (the latest figure made public), that reading too was not far off from the second quarter of 2016. After posting 101.7 in June 2016, the index began to improve, ranging between 102.1 and 104.4 from July 2016 to November 2018.

But after reaching 104.1 in November 2018, it fell to 103.9 in December 2018 and declined sharply to 101.9 in January 2019.

The base level for the index is the nation’s 2015 production capacity, which was set at 100 as the barometer. The statistics indicate that the monthly output of manufacturers has been in a slump since late 2018, with the index approaching the level where it stood four years ago.

In a similar vein, the index for labor productivity — which means output per worker for a certain period — stayed at 111.7 (basis is in 2015) during the fourth quarter of 2018 (the latest figure made public), marking the lowest level since the first quarter of 2018, when it posted 105.9. The quarterly indexes for the second and third quarters of last year recorded 112.0 and 112.4, respectively.

Industry insiders say the manufacturing industry is in the doldrums because of drastic hikes in the statutory minimum wage and new legislation limiting overtime hours.

As of July 2018, businesses whose payrolls have 300 workers or more cannot have their employees work more than 52 hours per week. Formerly, the ceiling was 68 hours.

Businesses whose workforces consist of 50 to 299 workers will be subject to the revised Labor Standards Act from the beginning of 2020.

The minimum wage rose to 8,350 won ($7.00) this year, as compared with 7,530 won in 2018 and 6,470 won in 2017. For workers paid on a monthly basis, the minimum wage increased from 1.35 million per month in 2017 to 1.53 million in 2018 and 1.74 million in 2019.

“The minimum salary surged by 29 percent in only two years,” said a research analyst in Seoul. “The huge burden of personnel expenses in addition to slashed working hours is believed to have frustrated the overall management efficiency of businesses.”

A related warning from a state-funded think tank is drawing attention.

The Sejong City-based Korea Development Institute predicted in a recent report that the nation’s GDP growth will fall to 1.7 percent on average in the 2020s unless steps are taken to revitalize productivity by easing labor regulations and other regulations governing the finance and business sectors.

The KDI cited a comparison of the 36 members of the Organization for Economic Development and Cooperation, in which South Korea ranked 28th for deregulation with regard to labor, finance and business activities.

Should deregulation be carried out, the average growth rate will hover around 2.4 percent in the 2020s, the institute forecast.

The presidential office has yet to express willingness to make any changes to its labor standards, but has said it intends to focus its policies on the manufacturing sector in terms of reinvigorating business sentiment and suggesting new growth engines.

Likewise, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy on Monday has promised to announce a new policy vision for manufacturers in the coming weeks. The plan, it said, will usher in a “manufacturing renaissance” by guiding key industries and new industries in more strategic directions through 2030.

A research fellow in Sejong cited data from the Korea Customs Service showing the nation’s exports dropped by 6.8 percent on-year during the Jan. 1-May 10 period. “It may be difficult for the nation to attain the rank of ‘world’s No. 5 or No. 6 exporter’ this year and in the coming years,” he said.

He said it seemed that the crisis affecting mainly self-employed businesspeople and small businesses over the past year or two was spreading to bigger businesses because of huge labor costs.

By Kim Yon-se ([email protected])