Concerns are growing over the negative impact of the strengthening won on Korea’s exports, with expectations also being raised that a rise in the value of the currency will help boost investment and consumption.

The value of the won gained 1.16 percent against the US dollar over the past two weeks to close at 1,069.6 won per dollar in the Seoul foreign exchange market Friday.

It marked the second-steepest appreciation among the currencies of Group of 20 major economies following Mexico’s peso, which appreciated 1.27 percent against the greenback over the same period.

The Korean currency saw its value rise to the highest level in nearly three and a half years — 1,054.2 won per dollar — Wednesday before weakening somewhat in the following days amid heightened worries over a potential trade war between the US and China.

Experts say the won seems framed to continuously strengthen as financial and monetary policymakers here are under pressure to refrain from intervening in the foreign exchange market out of concerns the US might move to designate Korea a currency manipulator.

A possible dramatic easing of tensions on the Korean Peninsula in the wake of the planned summitry on dismantling Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal would serve to further boost the value of the won.

“The exchange rate is expected to touch 1,020 won per dollar this year,” said Min Kyung-won, an economist at Woori Bank.

The strengthening won, which would make Korean products more expensive abroad, is set to exacerbate the unfavorable environment surrounding the country’s exporters, which remain highly vulnerable to escalating trade disputes between the US and China.

Korea depends on the world’s two-biggest economies for nearly 40 percent of its total outbound shipments.

A report released last week by the Korea International Trade Association predicted that Asia’s fourth-largest economy might lose up to $36.7 billion in exports this year due to the escalation of the trade row touched off by US President Donald Trump’s protectionist measures.

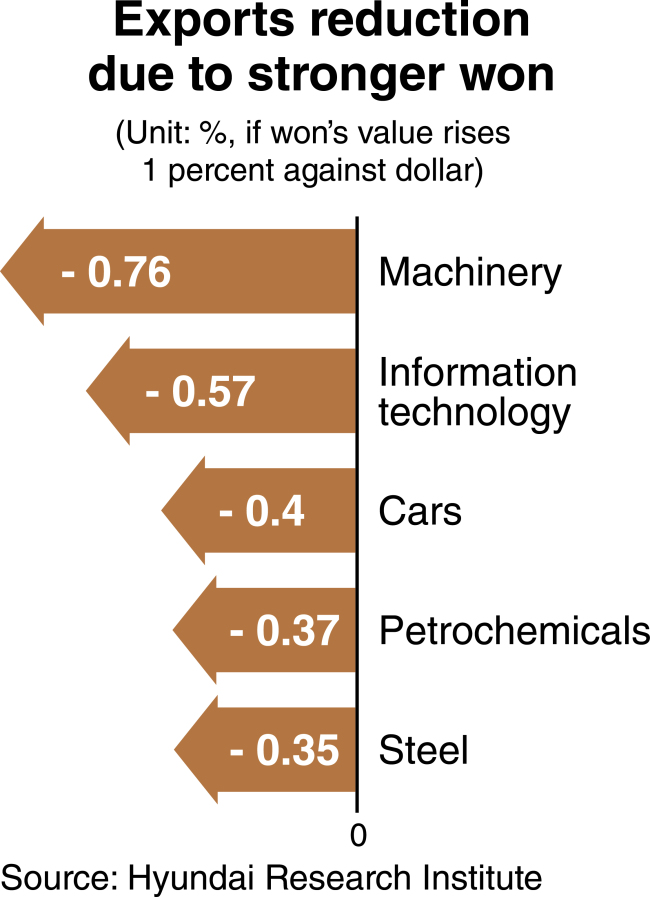

A recent study by the Hyundai Research Institute, a private think tank, estimated that a 1 percent rise in the value of the won against the dollar would result in reducing Korea’s overall exports by 0.51 percent.

By sector, outbound shipments would decrease 0.76 percent for machinery, 0.57 percent for information technology, 0.4 percent for automobiles, 0.37 percent for petrochemicals and 0.35 percent for steel.

Small and medium-sized firms focused on exports remain particularly vulnerable to the steep appreciation of the won as they are less prepared to cope with the impact from currency fluctuations.

An executive at a local manufacturer of electronic equipment expressed worries about the possibility that the exchange rate would fall below 1,050 won per dollar, set by his company as the bottom line for profitability.

“Sooner or later, we might be driven into exporting our products only to endure losses,” he said, asking not to be named.

The KITA report said the proper exchange rate for local exporters was around 1,073 won per dollar, with the rate for a break-even point averaging about 1,045 won.

The strengthening won coupled with mounting disputes between the US and China is casting a shadow on the government’s expectation that Korea’s exports would grow at least 4 percent this year following a 15.8 percent increase in 2017.

The slowdown in exports would also make it unachievable for the country’s gross domestic product to expand more than 3 percent this year as planned by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance.

Meanwhile, a report last week said that the strengthening of the won would also bring positive effects to the economy, indicating the rise in its value compared to other major currencies in recent years has led to lowering import prices and bolstering investment and consumption.

The further appreciation of the won “will likely serve as a factor to help increase investment in facilities and consumption in the private sector through falling prices of imported goods,” said the report from the National Assembly Budget Office.

It noted the weakening of the won would be more effective in decreasing domestic consumption than increasing outbound shipments.

Experts say the appreciation of the won could also lead to increasing the inflow of foreign capital, boosting local stock and bond markets.

Seoul seems ready to absorb a rise in the value of the won to clear suspicions of foreign exchange market intervention and free itself of the possibility of being named as a currency manipulator in the US Treasury report to be released later this month.

Officials here have repeatedly denied Korea agreed with the US to stop deliberately devaluing its currency in their negotiations on revising a bilateral free trade accord in return for an exemption from stiff steel tariffs.

But they have made it clear Korea is considering meeting requests from the US and the International Monetary Fund to reveal records of its intervention in the currency market, while stressing a decision on the concrete way of disclosure will be up to Seoul, not subject to foreign pressure.

Finance Minister Kim Dong-yeon told reporters last week the disclosure “will not be made in a way to infringe on our sovereignty regarding exchange rate.”

Kim is expected to meet with Bank of Korea Gov. Lee Ju-yeol this week to fix the time gap between interventions and the revelation of their records.

Most of G-20 members disclose records one month after intervention, with India and the US revealing them two and three months after, respectively.

Korea remains one of the three members of the group that have not made intervention records public. The others are China and Turkey.

By Kim Kyung-ho

([email protected])