The weakening of the won in recent weeks carries both benefits and risks for the Korean economy that is being held back by a simultaneous downturn in investment, consumption and exports.

Policymakers therefore face a thorny task to take proper steps in response to the weakening won that is set to have contradictory effects on the economy.

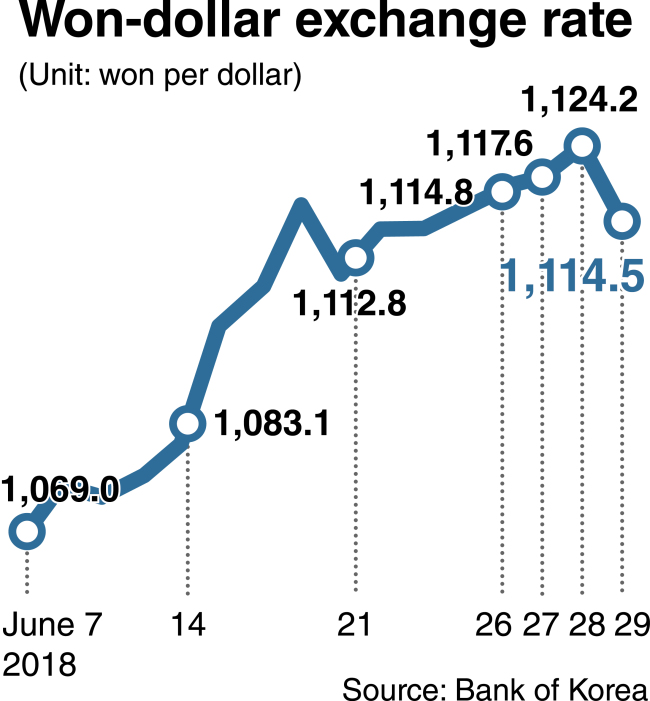

The value of the Korean currency against the dollar fell to an eight-month low of 1,124.2 won per dollar in the Seoul foreign exchange market on June 28 before rising somewhat to 1,114.5 won the following day. Over the previous 14 trading days, the won lost its value against the greenback by 5.1 percent.

Under usual conditions, the depreciation of the won can be seen as bringing more positive than negative effects to Korea’s export-dependent economy by enhancing the price competitiveness of the country’s exporters.

What is concerning, analysts note, is the steep pace with which the won has been weakening.

A comparison by Bloomberg of changes in the value of 20 major currencies against the dollar from May 31 to June 26 showed the won depreciated at the third-fastest pace of 3.32 percent.

The Argentine peso and South African rand were the only two currencies that lost more value than the won. The Turkish lira and Brazilian real depreciated 1.91 percent and 2.05 percent, respectively, against the greenback.

While the currency volatilities that hit most emerging economies earlier this year have lessened, the won is now in tune with the trend of depreciation against the dollar after remaining relatively strong partly due to reduced geopolitical risks on the Korean Peninsula.

According to data from the Bank of Korea, day-to-day changes in the won-dollar exchange rate widened from an average 0.34 percent in May to an average 0.44 percent during the period of June 1-27.

Analysts note a set of factors will likely precipitate the weakening of the won down the road, calling for measures to prevent a possible massive outflow of capital from the country.

“The won could weaken to 1,150 won per dollar within the year, if the trade tensions between the US and China continue to intensify,” said Ha Kun-hyung, an economist at Shinhan Investment Corp.

China’s move to devalue the yuan against the dollar to counter President Donald Trump’s trade pressure has served to push down the value of the won against the greenback in recent weeks. Experts note the local currency market is increasingly synchronized with the yuan’s movement as Korea depends on the Chinese market for nearly a quarter of its goods shipments abroad.

Concerns are growing that the escalating trade friction between the world’s two-biggest economies will weigh on the country’s exports.

According to government data released Sunday, Korea’s outbound shipments dropped 0.9 percent from a year earlier in June, marking the second monthly decrease this year following a 1.5 percent dip in April. A recent study by the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics and Trade forecast that the rate of on-year growth in the country’s exports would slide from 15.6 percent last year to 6 percent this year.

The prospect of a slowdown in exports coupled with deteriorating profits of Korea’s major companies has prompted foreign investors to sell off Korean shares.

Foreign investors have net-sold 3.8 trillion won ($3.4 billion) worth of Korean shares so far this year — nearly 1.6 trillion won in June alone.

“One of the fundamental reasons for the capital outflow is the weakening of confidence in local companies’ long-term profitability,” said Lee Jae-man, an analyst at Hana Financial Investment.

According to FnGuide, a financial information provider, the latest estimate of the combined operating profits of 132 major listed firms in the second quarter of the year reached 46.2 trillion won, down 8 percent from the 50.2 trillion won forecast at the start of the year.

A widening gap between interest rates in Korea and the US may also add to accelerating the capital outflow.

Policymakers seem ready to let the won continue to weaken.

“At some point, measures may need to be taken to stabilize the market,” said a Finance Ministry official, asking not to be named. But he added it would not be worrisome that the value of the won might fall further below the current level.

Pressured by the US and the International Monetary Fund, Seoul announced last month it would begin disclosing records on currency market interventions next year.

It may well expect measures to push up the value of the won will not be subject to punitive action from the US, which has focused on curbing moves by trading partners to devalue their currencies to help bolster exports.

What concerns policymakers is the possibility that the weakening won will be coupled with rising international oil prices to raise inflation. Korea’s consumer price hikes, which remained at 1 percent in January, reached 1.6 percent in April and 1.5 percent in May.

The upward trend in prices may lead the BOK to increase its base rate, which has been held at 1.5 percent since November.

The move may also be needed to narrow the rate gap with the US but would run the risk of further dampening domestic consumption and investment.

According to recent data from Statistics Korea, the country’s retail sales and facility investment decreased 1 percent and 3.2 percent on-month in May, respectively, marking the second and third monthly decline in a row.

By Kim Kyung-ho

([email protected])